Hurricanes have been battering Bermuda for centuries. While some of the most damaging storms of this century, such as Fabian (2003) and Gonzalo (2014) are well remembered by many of today’s residents, there were some equally ferocious cyclones that left a lasting impression on the people of past eras.

We look back, with the help of various sources, including accounts and memories of people who on two of the biggest, Hurricane Five in 1899 and the Havana-Bermuda Hurricane of 1926.

1899

On September 4, 1899, a nasty storm hammered Bermuda with strong winds for fully 12 hours. Residents were still focused on the clean-up effort, when the arrival of a Category 3 hurricane just eight days later caught them off guard.

Before it reached Bermuda, Hurricane Five, as it was known in the days before named storms, had already wreaked havoc in the Caribbean. Its 120mph winds had destroyed 200 houses in Anguilla, leaving 800 people homeless.

Terry Tucker, in her book Beware the Hurricane! quotes the American naturalist A.E. Verrill of Yale University, as stating that the 1899 hurricane was one of the most violent such storms on record.

Tucker’s book states: “The hurricane seems to have reached its height between 11pm and midnight (September 12-13) and continued with unabated violence until a little past 2am.

“At 3am, there was a lull for about half an hour, during which the rain that had fallen almost continuously for six hours, ceased and the wind shifted to northwest, rapidly growing its former strength.

“No abatement was noticed until about 8.30am, when the rain, which began again an hour or so previously, descended in white hissing sheets and lasted until 9am.”

A weather report by Walter S. Perinchief, principal keeper at Gibbs Hill Light Station, read: “Sept 13, 2am, hurricane with barometer at 27.73 inches.” It was the most powerful hurricane recorded in Bermuda up to that time.

Both ends of the island and the South Shore were severely impacted. Damage sustained at the Dockyard was estimated to run “into five figures”, while the Causeway was demolished by powerful waves at a cost of some £15,000, leaving St George’s cut off from the mainland.

Prospect Camp was described as looking “something as Alexandria after the bombardment”, Tucker wrote. Many large boulders on the South Shore were hurled inland by the violent seas and many boats were badly damaged.

“Great cedars were uprooted, ornamental and fruit trees were destroyed and wharves were washed out to sea,” the New York Times reported. In total, property damages amounted to approximately £100,000.

As noted by Dr Edward Harris, writing in his Heritage Matters column in The Royal Gazette, the storm damaged the Long Arm of the breakwater that protected Dockyard on its seaward, or southerly side, in a similar way to how it would go on to be impacted by Fabian more than a century later.

The 1899 storm was a direct hit. In a letter published by The Royal Gazette in 2014, John William Cox wrote: “I recall being told that as the eye of the hurricane of 1899 passed over the island on the night of September 12, my great-grandfather inspected the perimeter of his house and garden with a candle (this of course being during the days before electricity in Bermuda) and he noted that in the intense stillness of the eye, the candle never even flickered.”

1926

Bermuda suffered another direct hit from a Category 3 hurricane on October 22, 1926. Known as the Havana-Bermuda Hurricane, because it had caused devastation in Cuba earlier on its track, the storm tied with 1899 as the strongest storm to hit the island.

The anemometer at Dockyard measured windspeeds of 138mph before the device was destroyed by the storm. A British warship, the Valerian, sank five miles off Dockyard with 88 men lost and 21 survivors. Another ship, the cargo steamer, the SS Eastway went down close to Bermuda, with 22 of her crew of 35 perishing at sea.

Most of the damage occurred after the eye had passed over the island, as recorded by WH Potter in the Monthly Weather Review of October 1926.

“The calm centre was rather large, taking about 40 minutes to pass, the wind backing through northeast to north-northwest,” Potter described. “The wind blew harder and all the damage was done in the second half and its velocity was at least 120mph.

“Apart from two houses, unoccupied, destroyed in Hamilton, the damage, while rather large in the aggregate, was for the most part small individually. The roofs of probably 40 per cent of the houses were more or less damaged.

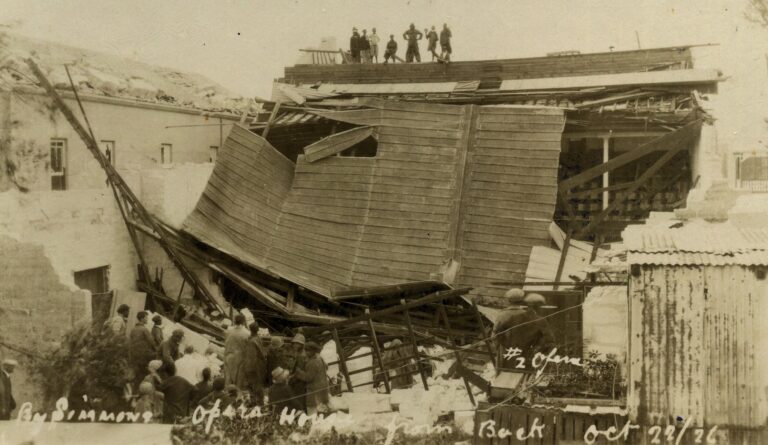

“No one was killed and one slightly injured, and there was no damage to speak of to the small boats in the harbour.” One of the notable buildings to suffer severe damage was the old Colonial Opera House in Victoria Street, Hamilton, the roof of which was destroyed.

In an article in The Royal Gazette in 2000, Thomas Aitchison recalled his experience of the 1926 storm. He was 11 at the time.

“As the morning wore on it felt as everything was going to be blown away,” he recalled. “Around the middle of the day it went very, very quiet. We undid one door and went out to take a look. I vividly recall there was a yellowish grey haze and everything was so still.

“From our cottage I could see for a distance of about a mile. It took about an hour for the eye to go over. You could see the storm moving closer by the line of trees bending as the storm hit them. I’ll never forget those trees swaying in the wind like blades of grass.

“So, we hurried back inside and battened down again. You never forget that feeling of the wind going from nothing to being in a great grip of ferocious wind. The rain was torrential.”

The scenes outside afterwards gave him a sense of the power of the hurricane. “Some big cedars, with trunks two to three feet thick, were lying flat on the ground with their roots sticking up in the air. They must have been several hundred years old and survived quite a few hurricanes before.”

Potter’s final observation in his report was this: “The telephone was hit hard, but the electric lights were on in Hamilton by 7pm on the 22nd, and here across the harbour by the next evening.”

It seems that Bermuda’s ability to bounce back quickly — after even the most ferocious storm — goes back a long way.