That there are gangs in Bermuda is not news – they were here long before the ill-advised assertion in the 1990s that there were no gangs, only “loosely organised groups”.

That these gangs are populated by young men who operate on the fringes of society is also not news. Between January 2009 and November this year there were 35 gun deaths attributed to gang violence in Bermuda, with another 90 people shot and injured. In the courts there have been 20 convictions for murder, 19 for attempted murder, 17 for unrelated firearms offences, and one conviction for manslaughter. During that time the police have seized 47 guns.

There have also been stabbings, drug busts, petty thefts, and myriad other offences that are associated with gangs and the crimes they commit.

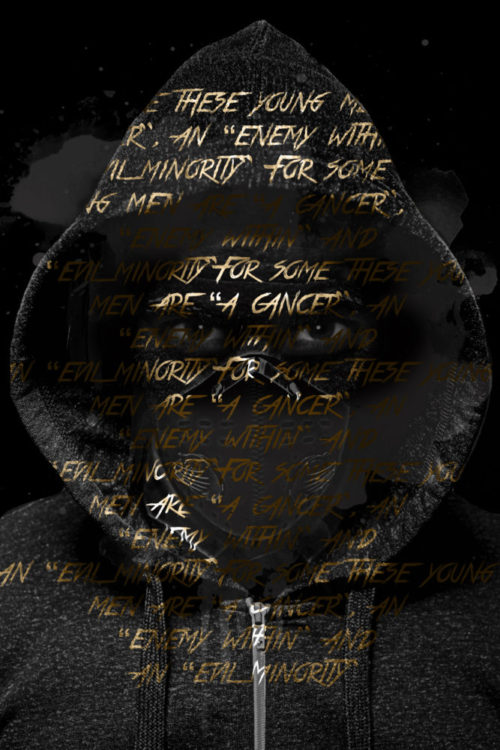

For some these young men are “a cancer”, an “enemy within” and an “evil minority” (The Royal Gazette editorial, Wednesday, June 1, 2016). Others take umbrage at this characterisation of the more marginalised members of our society, suggesting demonising them ignores the root causes behind gangs and deprives the community of its “grief and angst around these issues” (A.S. Simons, Letter to the Editor, June 3, 2016).

There are merits to both sides, although neither completely addresses the reality of the situation. On the one hand there is little understanding of, or appreciation for, how and why young men are being drawn into a life outside the boundaries of what is acceptable in civilised society.

On the other is the longstanding inability to address the issue honestly, if at all, which is not something that Bermuda, with its small close-knit community, has historically been good at; be that talking about gang violence or drink driving.

“I think for a long time people turned a blind eye,” said Antoine Daniels, the Assistant Commissioner of the Bermuda Police Service. “They said ‘this is Bermuda, it doesn’t happen here’, or the other one was ‘it doesn’t affect me’.”

The unwillingness to speak ill of the dead reflects the realities of living on a small island, but it also exacerbates the situation by papering over the cracks of the problem. Having honest conversations about the person who died and their lifestyle, while expressing sympathy for the family left behind, are not mutually exclusive.

Someone can be a “loving father or son” while also acting in such a way that their death or incarceration becomes a foregone conclusion. But, barring a few rare cases, people are not inherently evil, nor born killers. They do not grow up dreaming of being gangsters, but there is a moment when that becomes the most appealing, or sometimes only, avenue available to them.

It is in understanding that process, talking honestly about the realities of a life where anger dominates love, and learning how to change those realities that lies at the heart of reducing the violence that has gripped the island for the past decade and more.

The Community Activist – Desmond Crockwell

Desmond Crockwell is a passionate believer in prevention being better than punishment; unfortunately he believes he is in the minority and that people in Bermuda do not care enough to stop gang violence from happening.

“The problem is the attitude people have; ‘as long as it doesn’t happen to me, or my immediate family, I really don’t care’,” he said. “Our children can die and we do nothing. No one is marching up and down for that. Two guys want to get married and people are marching up and down.

“We [Bermudians] are very proud, but we don’t want to get our hands dirty. We’ll talk about everybody in the world, we love running our mouths, but tell us to go out there and do something, and it’s a whole different story. We need to make sacrifices. If we don’t we’ll just continue to talk.”

For Desmond, there is no mystery in what propels young men towards gangs. He has been there and come out the other side. He understands the anger and the frustration that come from feeling marginalised and isolated in your own country; from feeling trapped by a lack of opportunities and forgotten by a political class that seemingly does not care – or cares only when it comes to photo opportunities and good publicity.

Desmond sees the decades of investment in the court building, police station, airport and sporting events as ample evidence of where the Government’s priorities lie, and he does not believe it is with those that are suffering the most.

“Government has to take a lot of the blame for the way things are,” he said. “They spend millions on prosecutions but tell us [in prevention] that there is no money, so I know you don’t care.

“Where are the community centres? Where are the schools for troubled kids? The sporting clubs are kicking them out. There is nowhere for them to go to vent their anger, their frustrations.”

Ultimately Desmond believes the solution lies in a reworking of priorities and investment, not just of money but of time. The emotional needs of children coming from broken homes require just as much focus as those whose anger stems from an education system that has let them down badly.

“The feeling [in the gangs] is ‘you’re going to wait for me to shoot somebody before you recognise I’m here’,” he said. “You’re not coming to me, so I have to shoot now before you even understand that I’m frustrated.

“We need to talk to them to understand why they are so upset. There all these underlying issues that we don’t know about, that we don’t take the time to know about. Sometimes they just need someone to talk to because otherwise they are bottling up that anger – and it comes out.

“Not listening has a serious impact on our community. Sometimes it’s just a case of talking. They might have trouble at home, be hungry, and they are angry because they don’t think they can tell anyone. There are underlying things at home that we don’t know about, which is why we need facilities in these areas where children can go to be safe, to talk to people.”

For Desmond, one of the most telling moments in his life came through such an opportunity: a chat with a neighbour who told him to focus on the positive aspects of his own character.

“Those people [the ones who listen] are the heroes,” he said. “A guy no one would have thought about said to me ‘listen Desy man, you’re a good person you know I’ve seen you do good, all those good things that you’ve done, and this [the bad] is what you want to dwell on? Because everyone is dwelling on it? You need to see yourself as this, then you can help the ones coming behind you’.

“You can’t tell a youth ‘you’re a bad child’. You can say ‘you’ve done a bad thing’, but not ‘you’re a bad person’. There’s a difference. There has to be a difference in the way we talk about our children. If you tell a child ‘you’re never going to make it’, eventually they will believe you. Tell a child they’re trying, they’ll keep trying until they make it.

“The little things we say, the little things we plant into our children’s minds, the places that we take them has a lot to do with how they think about themselves. That is something I really try to emphasise; we don’t have bad people, just bad choices.

“What we do and tell them [the youth] matters. We can’t just keep telling them ‘straighten up before I help you’.”

The Gang Member – Anonymous

It is difficult to get gang members to talk for obvious reasons. The fear of being identified, of being accused of talking outside the gang, for bringing unnecessary attention to themselves – all of these things plays a part.

Still, to truly understand the reasons someone may have for joining a gang you have to go to the source.

The concerns lessen for those who have been caught and now reside at Westgate, although they never go away, which is why this interview was conducted with the understanding that the person consenting to it would not be identified in any way.

How did you get started in a gang?

“Speaking on my perspective, coming up some people’s not really got it [academics], and so you’re struggling. A lot of us turned to hanging on the streets, then it leads to selling drugs and some people get the impression…they feel they are upgrading themselves.

“I guess people just get over their heads with certain things and they feel that they are bigger than other people, and it becomes a pride thing.

“I wanted to be a mechanic; I used to like to fix bikes. But I got caught living in the fast lane by selling drugs, and I thought that was the right way to go because I was waiting for a paycheque. I was getting that in a week what I was earning in a month. So I was hooked on that instead of the job, but now I feel it and I have regrets.

“I wish I had…it was a good job and it was a well-paying one, but I just got caught in the fast lane. But that happens to a lot of people. If you can make $500 in a day, instead of waiting a whole week, then why not go for that?”

How do you get the gang members today to understand the reality of what they’re doing?

“The only way they will get understanding is if they get it from somebody who has been there, has been in the lifestyle, thought that what they were doing was right, but end up finding out down the line that it’s not right, because friends that you think have got your back out there, they don’t have your back when you are in jail.

“They [friends] don’t put money at the canteen for you, they don’t phone, half of them you can’t even get to come visit. And the people that are looking out for you are the ones that are hurting – your family. They are the ones that will be there for you for the rest of your life. But the hurt, it always leads back to the family members.”

Isn’t providing for family what it’s all about?

“To a certain extent because at the time you think you’re doing the right thing. But then the shoe falls off the foot and you find out that path was really the one you shouldn’t have been walking down. That’s when reality sets in.

“Some families wouldn’t know because a lot of men are not going to go home and tell their momma ‘somebody’s trying to kill me’ or ‘I’m in this lifestyle’. They try to shield it from their family, and if something happens around the house, obviously they [the family] are going to be very frightened.

“It does have an effect on families. They have to live with that for the rest of their life; they’re not going to forget what happened. I’ve been shot at. It’s not a nice feeling, it’s not a nice sound. I’m just lucky I’m here to talk about it.”

How do you stop the younger generation wasting their lives?

“The only thing I can suggest, as someone who has lived that lifestyle, is to show them the things that have happened in my life. Show them that, all right, cool, you might be living your life, getting away with doing your thing, bragging to your girl, your boy. You think they’ve got your back.

“Those girls ain’t going to be your girl. She’ll be somebody else’s girl, and you’re going to have problems in jail. If they feel that that kind of lifestyle is cool, with one of their brethrens in jail doing a life sentence, then they’ve got it wrong, they’ve got it twisted.

“I’ve heard a lot of guys say ‘I’ll go jail’, but they don’t know – even the hardest of guys in here break down crying.”

What would you say to them if you could?

“I’d want them to know [that] no money can amount to human life and if the youths are thinking about picking up a gun, to just to show your girl that you’re some gangster, or whatever they have in their mind, let it go. Because when you’re sitting up in this jail cell, it’s not a good thing. You have no friends around you and when you’re in that quiet time by yourself, that’s when reality kicks in and you know you’re not going home.

“I would tell them get out, get an education, raise your family the right way, rather than have your child come and visit you in jail.”

The Family Member – Arreta Furbert

Arreta Furbert has endured a mind-numbing grief that most mothers could not fathom.

In October last year, her 19-year-old son, Isaiah, was shot dead in his bedroom as she folded his laundry in the room next door.

She watched helplessly and hysterically as EMTs tried desperately to save her only son’s life before rushing him to hospital where she was told he had died.

Just nine months later, Arreta saw her son’s best friend, Jahcari Francis, 20, murdered in almost identical fashion in the same Upland Street home as they sat down to dinner.

Police have yet to charge anyone with either murder, but the grieving mother rejects assumptions that her teenage son was mixed up in the tit-for-tat gang lifestyle.

She admits he had enemies, but insists his allegiance to the St Monica’s area was borne solely from family and friends that he grew up with, rather than any criminal enterprise.

“I never felt worried that my son was in a gang; they were throwing up the signs of where they came from in middle school, but I did not see that as them being part of a gang,” Arreta said.

“For Isaiah, it was where he was from. His grandmother grew up on Mission Lane and he would go up there to see his uncle. That recognition of 42 and 42nd Street to him was not what it may seem to a stranger.

“A lot of the tension with others stemmed from when they were at school and aged 11 or 12; punch-ups in the schoolyard and things like that. Call it naivety on my part, but I never took it to heart. I never imagined anything like this would ever happen.”

Arreta and Isaiah had lived under the same roof every day of the teenager’s life.

“As long as I can remember, it was always just me and Isaiah,” she said. “I worked two jobs all that time and he always wanted to be at home,” she said. “His friends would come over; they were always at our place, and that was just the way it was.

“I didn’t want him hanging out on walls; I wanted to have him in my sights. My mother was always there too; we were a very close family.”

In July 2016 Arreta, her elderly mother and Isaiah moved back to Upland Street for a second spell.

She said: “We had toyed around with the idea of him going to Canada after he finished school, because he was a Canadian citizen through me, and I tried to push him in the direction of navigation and ships.

“But he did not want to leave. He wanted to go fishing with his dad and spend time with his friends.

“Then things started to go a little haywire. Before, he was never really involved in the street; he never really hung out at clubs or football games. But then in the summer, before his death, he started going to things like Beachfest, Cup Match and Non Mariners.

“I knew there were people who did not like him and he was smoking weed, but I felt I was in control. He wasn’t stealing or anything like that. I would ask him what their beef was; he just said they were just jealous.

“He sometimes told us that he was not going to live to be an old man. Now that seems quite prophetic.”

Arreta insists she kept close tabs on her son, always checking his drawers and pockets for any signs of trouble.

“I don’t think I was complacent,” she said. “I felt like I was doing everything I needed to. Isaiah was not a good liar, so I never felt he was drug dealing or anything like that.

“His behaviour was not strange. Some people had said to me you need to get him off island, but I remember him saying he would not let them chase him away. He said he had not done anything wrong. Even now I cannot figure out what the hatred was all about.”

Arreta described her son as a “good soul” who was popular and would give friends the shirt off his back.

“I feel like I ran out of time with Isaiah; they pulled the rug from under me,” she said. “He was no angel but I keep thinking, if only I had just had a little bit more time with him.

“I would like some kind of closure. I want to see the man who did this to my son and ask why. I just don’t understand, but I refuse to let them win.”

The Police Officer – Assistant Commissioner Antoine Daniels, Bermuda Police Service

For Mr Daniels, the fight to combat the gang problem in Bermuda begins in the schools.

With gang members getting ever younger, the Assistant Commissioner is under no illusions as to the task the police face in helping to solve the problem.

“Bermuda is no different from any other Western civilisation, where you get a lot of the kids displaying a lot of antisocial behaviour and delinquency if you don’t get into them quickly,” Mr Daniels said.

“That’s why we gear the gang resistance programme towards Primary 6 and M1. The 10, 11 and 12-year-olds; that’s the time of development where you see them bearing those certain characteristics.”

Research tells the police that children primarily join gangs for one of three reasons: social status, financial need and fear. On top of that, there is the disenfranchisement that comes from feeling that society has no place for them, that there is no hope for the future, so they create an alternative society.

“I was listening to the radio the other day where they were interviewing two teachers who were talking about the students in their classroom, and that they have to prepare them to learn. They arrive at school and they’re not ready; they’re hungry, there is trauma at home. The teachers have to deal with this before they can even teach.

“This is the type of situation that you’re dealing with in Bermuda, so it’s not lost on me that we have some serious problems.”

While the traditional aspect of policing – catch and convict – will always form the largest part of Mr Daniels’s focus, there is an appreciation, too, that the police can have a positive influence early on by working with charities such as Family Centre and Mirrors to provide safe and supportive spaces, mentorship and coaching for children that might not otherwise have access to those things.

Programmes such as the Youth Leadership Academy, Homework Academy and Beyond Rugby are important, so too the Gang Taskforce, which at the height of the gang violence went into the schools to educate teachers and parents about what was happening.

“We went to the high schools and middle schools [public and private] and had a real heart-to-heart with a lot of the teachers,” Mr Daniels said. “We’d bring them to the assembly and point out the gang paraphernalia that the children had on, and they [the teachers] didn’t even realise it.

“At some schools we found that students would form in certain areas of the school where there were gang symbols on the walls. We had those painted over them to try and break that up.

“It’s very sensitive how you do it. You never want to come out and say X-school is more gang-culture than Y-school. Although we know and recognise what is going on in those schools, we try and work with the principals and student body to resolve those various issues.”

Building trust in the community is also essential, but Mr Daniels also knows that people have to want to help themselves. “The biggest thing for me is to try and get people to understand that handcuffs are not going to solve the problem,” he said.

“We try to show the community that if you continually turn a blind eye to what’s going on, one day it may be on your doorstep, and that’s one of the biggest messages I try to get out there. Either get involved voluntarily, or you might get involved through some type of mishap. It’s not a threat, it’s not trying to scare people, it’s the reality of what’s going on. And I’ve seen that first-hand.”

The Politician – Wayne Caines, Minister of National Security

If people want practical solutions to the problem of gang violence, then Wayne Caines knows exactly where they need to start looking – at themselves.

The Minister of National Security believes that while the Government has a responsibility to help to solve the issue, with improving education being a major focus, communities must also take a greater role in preventing young men from falling into a lifestyle that too often ends in misery and death for those around them.

“In Bermuda, everyone wants to know what are the practical things we can do? On a practical level, we have to hold our sons accountable for their behaviour,” the minister said. “We cannot give safe harbour to anyone that is doing antisocial behaviour and it is as simple as allowing someone to use a car that is uninsured and unlicensed. This is fighting in the neighbourhood, this is selling drugs; all of these things are interconnected and basic things that we can do.

“Our parents, our community, we have to hold everyone accountable for their actions. We have to make sure we create safe environments for our young sons. The sporting groups have to create an environment [that is safe] from first thing in the morning to last thing at night. A lot of our young men do not have safe environments, so we have to create surrogate families; whether it is our church, it’s the sporting groups, but they have to have a safe environment where they can develop, mentally and socially.”

For the minister, the disintegration of the family unit is crucial to understanding the problem that the island faces, as is understanding the psyche of the young men that are attracted to that lifestyle.

“We have to look, the black community specifically, we have to look at making stronger families because something that is crystal clear, when a young man does not have a father in the home, he is much more likely to seek solace, comfort and guidance from those in his peer group,” Mr Caines said. “The Government will do its piece, community clubs should be held to account to their piece, but the last piece is the family. The family has to be encouraged to make wise decisions; we have to encourage the family to play an integral part in healing our country.

“That goes to the next thing, mentorship. A lot of times we want performance without development. We have to ensure that we have every able-bodied man, whether they are black or white, getting back into our community and mentoring young men. We have a mentality of ‘that’s not my son’, or ‘that’s what’s happening in the back of town or Somerset’. We have to create a model of mentorship…I’m talking things outside of what the Government is already doing.”

One thing the minister is not convinced by is the argument that successive governments have been more focused on punishment rather than prevention. What he does believe is that a section of society was ignored in the race for economic growth.

“The reality of it is that for a very long time we have been successful as a business jurisdiction, a blue-chip jurisdiction,” he said. “We have allowed our success to permeate the business sphere, but the family was left behind. We are seeing the manifestation of the neglect to the social fabric of our country, but all is not lost. We have things to put in place that can solve this crisis and I believe together we can do it. I believe there is an opportunity to heal Bermuda.

“I would say that we have never looked at this as a public health crisis. We have to take a more clinical approach, we have to deconstruct the psyche of those that are committing the violence and we have to incorporate what we have learnt, including from the police, and put all the different elements together.

“The Government has a plan, but as far as the community is concerned, everyone has to row in together. Sport clubs, families, churches have to come together in a holistic approach to solve the problem.”

There have been 35 gun murders in Bermuda since May 22, 2009 in 34 shooting incidents*

Malcolm Augustus

Deshaun Jerry Berkley

Stefan Burgess

Garry “Fingas” Cann

David Clarke

Fiqre Crockwell

Jonathan Dill

Patrick Dill

Prince Barrington Edness

Colford Ferguson

Jahcari Francis

Isaiah Furbert

Rico Furbert

Kumi Harford

James Lawes

Jahmiko LeShore

George Lynch

Dekimo “Purple” Martin

Freddy Maybury

Jason Mello

Shane Minors

Haile Outerbridge

Jahni Outerbridge

Michael Phillips

Perry Mosley Puckerin

Raymond Troy “Yankee” Rawlins

Erin Lee Richardson

Joshua Robinson

Kenwandee “Wheels” Robinson

Randy Robinson

Jason Smith

Morlan Steede

Lorenzo Stovell

Rickai Swan

Kimwandae Walker

* This list does not include Shaki Crockwell, who was shot in 2007 before the big outbreak of violence started (his killer, Derek Spalding, was sentenced to life behind bars, and must serve 25 before becoming eligible for parole) or Jason Lightbourne, who was fatally shot in 2006 (Prince Edness was charged and acquitted in November, 2014 – shortly before his own murder)

According to people who work with gangs, there are several reasons why children join them. These are the most popular:

- For money, jewellery, respect and power

- For a sense of belonging

- As a result of the neighbourhood where they live

- For protection

- Because they were forced into it

- Out of boredom

In the battle parents face in keeping children out of trouble, here are some tips from the Gang Prevention Unit on how you can spot if children are going down the wrong path.

- Watch their friends and associations carefully and observe whether they move around the Island with friends for protection

- Be concerned if they do not want to travel to certain areas

- Monitor Facebook postings

- Watch out for the use of multiple cell phones, which can be a sign of drug dealing

- Look out for signs of drug and alcohol abuse and failing schoolwork

- Be wary of them throwing up gang signs and being made aware of gang-related incidents instantly.

The best ways to prevent young people getting caught up in gangs are to:

- Give them as much encouragement as possible and encourage extra-curricular activities such as church and youth groups and sport

- Encourage them to stay focused at school

- Discuss the consequences of gang life and what it leads to

- Open their eyes as much as possible about other countries and cultures

- Discourage any glorification of gangs, guns and drugs

- Monitor what they see and listen to on the television and internet

This article was featured in the December 2017, RG Winter Magazine.